Research project (2012–2016)

Preserved studio-space of sculptor Ruthild Hahne, Berlin

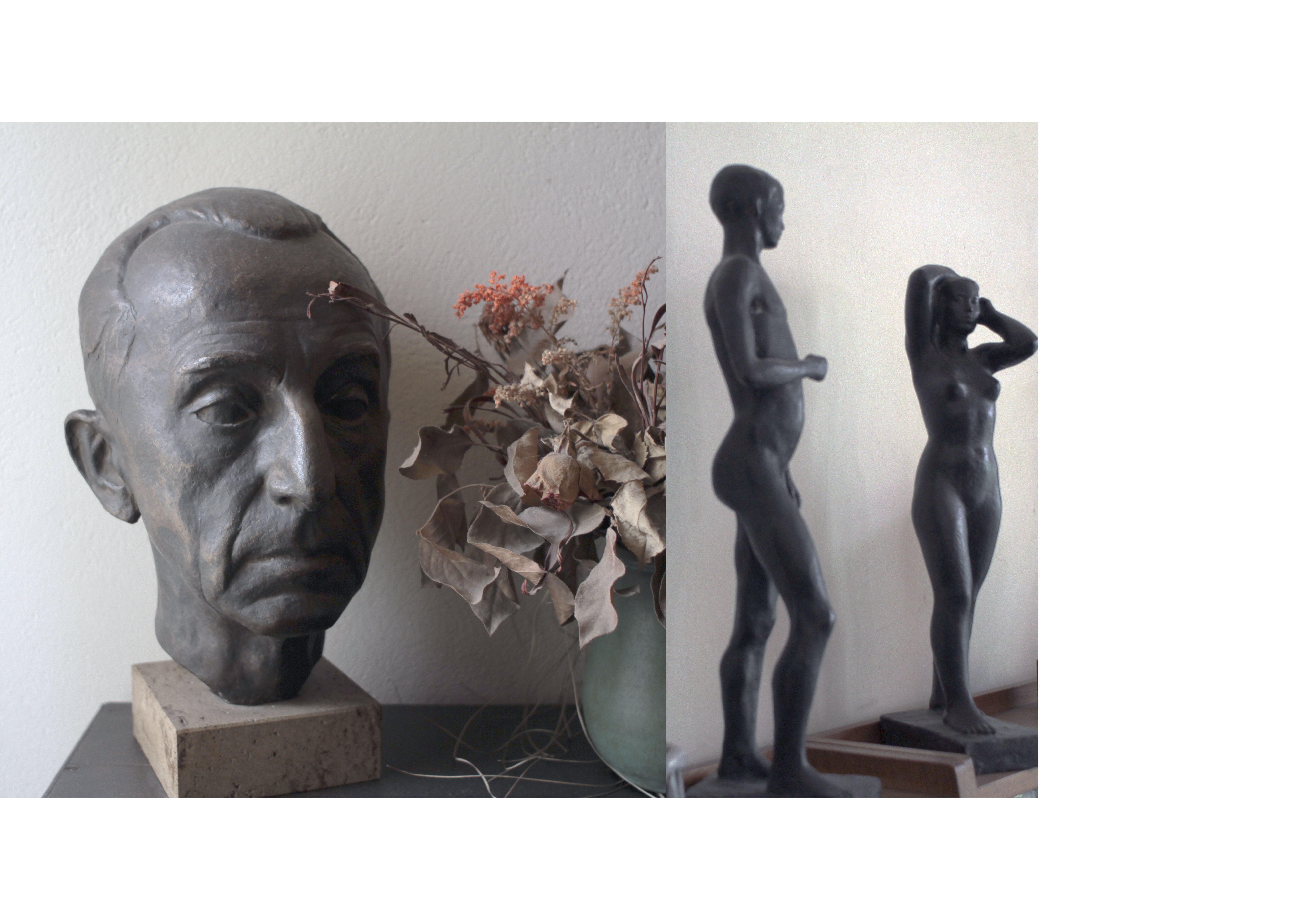

Preserved studio of Gustav Seitz, Hamburg

13 photo collages, digital prints, A2

Interview with Stephan Hahne (Video)

Sculpture, the Mnemosyne

– a kind of intro –

When I was ten years old, my family into a house with a spacious garden in a quiet street in the western outskirts of Hamburg. The house is owned by a foundation that manages the bequest of the sculptor Gustav Seitz, who had lived here until his death in 1969. His studio, an annex to the older main building which our family hadn’t rented, contains many of Seitz’ plaster originals, small terracottas, numerous portrait heads, drawings, documents and personal items.

It was probably the first substantial artistic oevre I had seen in my life and I cannot say that I was overly impressed. Even when I decided to go to art school and was busy preparing my first portfolio, I still didn’t care to take a closer look at Seitz’ works; neither his voluptuous female figures, love-making couples, or even the various portraits of Berthold Brecht, Heinrich and Thomas Mann and Ernst Bloch caught my attention. Seitz had devoted himself entirely to an exploration of the human form, realistic or typifying in his portraits, while developing degrees of abstraction in his standing or sitting figures over the years.

I think I had forgotten about him completely, and so has art-history and the “contemporary” art world.

Much later, having become an angry student at the University of the Arts in Berlin, I came across the name Gustav Seitz while researching in the university archives for documentation of historical student dissent and protest. His name came up in the context of a number of politically motivated staff lay-offs that had taken place in the early stages of the Cold War. Although not exactly a very political person, Seitz, who had been appointed honorary member of the Academy of Arts (re-opened in 1949 by the East-German government and intended to be a pan-german cultural institution), was asked by the city magistrate of West-Berlin to denounce his membership in the “east-zonal” academy, as such a membership was “not in compliance with his function as a teacher at the (West-Berlin) art school.”

Seitz’ response to the magistrate speaks of his belief in the principles of personal freedom and his conviction that the sharpening divide between east and west should be countered through the cooperation and activity of individual citizens. Seitz shared these opinions with his colleagues Heinrich Ehmsen, Waldemar Grzimek and Oskar Nerlinger, all of whom were dismissed between 1949 and 1951 for similar reasons. Gustav Seitz remained a member of the Academy of Arts and moved to the eastern part of the city, but in 1958 he left Berlin, to take up a post at the Hamburg School of Art. The climate of increasingly hysterical disputes on cultural policies (essentially the debate on formalism versus realism) and the political streamlining of the arts towards representative socialist realism in the 1950s made it difficult for Seitz to follow his intentions as artist, teacher and cultural organizer. Having been awarded the national arts prize of the GDR and having worked on a number of state commissions, Seitz had earlier declined to accept a post at the art school in Kassel, which was based on the condition that he left the GDR with a “political blast”, as Seitz called it. He did not want to seem “unthankful”.

While at home for christmas, I decided that I should take a second look at the sculptures in the small next-door studio. I am not exactly an expert in sculpture, and in fact I have worked with almost every other artistic media except this one. Nor am I an art-historian with a good overview of figurative sculpture. But in trying to locate Gustav Seitz‘ work – not only his material oevre but all accounts of his humanist position, his biography – in the web of personal connections, political history, cultural climates during his life-time, I keep discovering links, and parallels to his colleagues and friends and in turn, their bodies of art-works, histories and tragedies as artists and political subjects unfold, while catalogues from the art library and archive documents pile up on my desk.

Where to start. Perhaps I could recount chronologically and talk about some of those who were with Seitz’ at the Berlin school of art before and during the Third Reich; speculating how they lived, worked, and about their active or silent resistance; what they learned from each other and from their teachers Wilhelm Gerstel, Edwin Scharff, Ludwig Gies, whose sculptural works were removed from the public museums and shown in the ‘Degenerate Art’ exhibitions; or how they worked in the shadow of the oppressive NS cultural regime, or were banned from their profession. I could retell how many of them, like Gustav Seitz, lost major parts of their works during the WW2 bombing of Berlin, or how some lost their lives, like the resistance fighter Kurt Schumacher and Hermann Blumenthal, who died as a soldier.

Where to start.

Some are hard to trace and have been forgotten, while others became well established artists in the two Germanies. Among them are Fritz Cremer and Waldemar Grzimek. Should I concentrate on these two, friends and colleagues of Seitz, all three of whom were educated in the sculpture class of Wilhelm Gerstel at the Vereinigte Staatsschulen, the Berlin art school, in the 1930s? They all inherited the same formal principles of figuration from their teacher, and an inclination towards the search for the human condition in posture, gesture and tectonic structure.

Among Fritz Cremer’s works one can find more aspects of struggle, grief and political intent, and in his writings he speaks of class struggle and dialectics. He shared with Seitz an admiration for the artist Käthe Kollwitz.

But I have lost sight of his artwork. I should talk about Gustav Seitz’ fascination with Brecht’s face, a recurring motive in many drawings and portraits, even long after Brecht had passed away. And Käthe Kollwitz, sitting. Her full figure portrait can still be found in Kollwitzplatz in Prenzlauer Berg, Berlin, commissioned by the East-Berlin administration in the early 50’s.

Many similarities, shared motifs and motivations can be found when comparing Grzimek’s, Cremer’s and Seitz’ sculpture, and Barlachs and Kollwitz’ influences exist in the work of all three, I think.

All of them worked at the margins of official art-political doctrines, working on prestigious official commissions such as the antifascist memorials in Halle and in the concentration camps in Buchenwald, Sachsenhausen, Ravensbrück and Weisswasser, struggling with official demands for heroic figuration on one side, or trying to distinguish themselves from the dominant non-figurative abstraction on the other.

A female colleague, another fellow student from the Gerstel class was Ruthild Hahne. She and Fritz Cremer, together with the painter Fritz Duda and others had formed the Red Student League, a communist club at the art school during the early 1930s. They continued their antifascist activities in one way or the other over the following years. Fritz Cremer shared his art school studio with Kurt Schumacher, a student in the master class of Ludwig Gies. The studio served as an illegal “postbox”, a place for members of the resistance network to exchange information and material. Dancer and sculptor Oda Schottmöller went in and out here. Model for Fritz Cremer, she received lectures in sculpture from Kurt Schumacher. It is known that Waldemar Grzimek, a very young student at that time, was in touch with and taking part in some of the discussions and activities within the wider network. When the resistance circle (dubbed Rote Kapelle by the Gestapo) was discovered, Kurt Schumacher, his wife Elisabeth, Oda Schottmöller and many others were executed. Ruthild Hahne and Hanna Berger, Fritz Cremers wife, were among those who were imprisoned but could escape during the chaos of the bombing. Where was Gustav Seitz during these years, I wonder. Maybe working away in his studio, he did not quite realize what his colleagues were busy with. And if he had known, would he and his newly wed wife Luise Zauleck have joined the illegal circles? Nothing in his work speaks of such resistance. But again, nothing in his works speaks for any kind of participation in the streamlined Nazi culture except for one relief in Hitlers 1936 Olympic stadium. Another post-war relief work of 1946 is documented showing five hanged figures, most likely inspired by a Villon ballad, a medieval poet Seitz admired. This may have been a reminiscence to the dead colleagues from the art school or their wider circle, as some of them had been hanged in the Plötzensee prison.

However, this remains speculation and for reasons unknown, this work was destroyed.

Some years later, Ruthild Hahne – then teacher at the east Berlin art school- and Gustav Seitz – then teacher at the west Berlin art school – took part in a competition for a state commissioned Thälmann memorial. Ruthild Hahne won the competition while Seitz proposal was rejected. It was to become the tragedy of her life that despite of her yearlong work on this monumental sculpture group, its realization was finally cancelled, as the Berlin wall was built on the site planned for the monument.

For Seitz, just the participation in the Thälmann competition got him a first reprimand from the city magistrate. Another draft for the Marx-Engels monument opposite the east Berlin Palast der Republik remained unrealised. Those are the only obvious political motives within Seitz work, both unsuccessful, he seems to have refrained from further attempts in that direction.

I tend to sculpt this virtual Gustav Seitz in the way that I would have liked him to be. I strive to see in his work the concerns for the essential, an ethical and in fact political – though not party-affiliated – straight-forwardness, mediated and distributed through his sculpture. Or rather, born through his sculptures. His intensive work on the vagrant Villon figure might be seen as evidence for Seitz search, his quiet non-conformism and independent attitude.

Whatever it is in his work, I seem to have caught a glimpse of it only now. And in the same way, I think that it is possible to look at many sculptures, and particularly sculptures in public space, which by nature have undergone various stages of public dispute, legitimation, political-administrational procedures so that their actual form and their realization can in fact tell us the full story of their times.